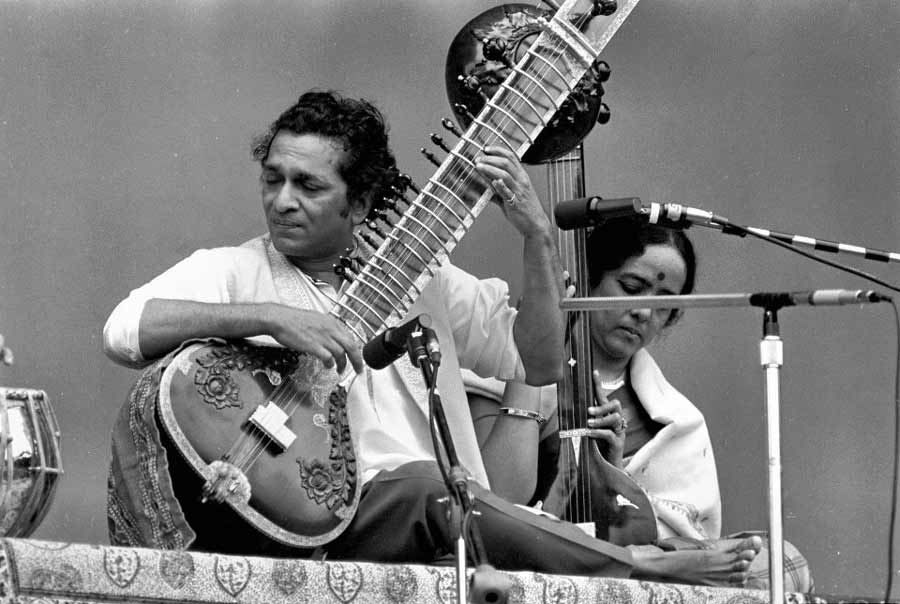

In the winter of 1967-68, I went to a Ravi Shankar concert in Boston. The auditorium was packed with aficionados of Indian classical music, curiosity seekers, trend followers, and a boatload of hippies and rock fans. Nine of ten, I would estimate, were under 30, and most of them inhabited the new landscape called ‘counterculture’. Without trying, and with considerable reluctance, Shankar had become a superstar, having made his historic appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival that June, at the onset of the Summer of Love. His performance had blown thousands of minds, and many times more were blown when D. A. Pennebaker’s groundbreaking documentary Monterey Pop was released the following year. The film included performances by icons like Simon & Garfunkel, the Jefferson Airplane, the Who, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, who famously lit his guitar on fire and smashed it to pieces. But audiences left the theater with their minds blown by the climactic moments of the film, about 18 minutes of Shankar’s stunning four-hour set.

Before starting that Boston performance, Shankar addressed the audience. He said he’d learned that young people were taking drugs before coming to his concerts, thinking they would appreciate the music more if they were stoned. He did not like that idea. About 48 at the time, and therefore an elder to the baby boomers in attendance, he said we should come to the music with clean nervous systems, and if we wanted to expand our minds we should do so with meditation and yoga. You could practically hear a collective “Bummer!” emanating from the altered brains of the disappointed.

But others had a different reaction. For them, Shankar’s statement confirmed something they had come to suspect: that the psychedelic experience was a window into states of consciousness that might be attained safer and more reliably through the same ancient wisdom that had nurtured, and perhaps given rise to, the music we had come to hear. Yehudi Menuhin, the great violinist who had first invited Shankar to the West in the mid-50s, said in his memoir that the purpose of Indian music is “to make one sensitive to the infinite within one, to unite one’s breath with the breath of space, one’s vibrations with the vibrations of the cosmos.”

Many listeners felt that vibrational shift, and the euphoria it generated triggered a widespread exploration of India’s spiritual treasures. For that reason, Ravi Shankar should be remembered as much for his contribution to contemporary spirituality as for his extraordinary virtuosity, his prolific output as a composer of concert and film music and his role in promoting his country’s musical heritage and world music in general.

Shankar, who died at age 92 in 2012, was born to Bengali parents living in Benares (now Varanasi) in 1920, at the height of the British Raj. At 10 he started touring India and Europe with his brother Uday Shankar’s famous dance troupe. He switched from dance to sitar when he was 18 and, after six years of study with the master Allauddin Khan, he began performing and composing. Among other works, he created the score for Satyajit Ray’s sublime Apu Trilogy. It was while viewing those three classic black and white films that many Westerners first became drawn to Indian culture, and Shankar’s subtle but indelible music was a major part of the enchantment.

Not long after India achieved its independence from Britain, Shankar served for seven years as director of All India Radio. During his tenure, in 1952, he met Yehudi Menuhin when the violin master visited New Delhi. Menuhin (who also brought hatha yoga master B.K.S. Iyengar to the West) recognized genius when he saw it; he paved the way for Shankar to come to America in 1956. With the help of Menuhin’s imprimatur, Shankar gave classical music aficionados an appreciation for Indian music. The two virtuosos teamed up for an historic collaboration, appropriately titled West Meets East, which won the 1967 Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance. As it happens, that same year, the Beatles won the Album of the Year Grammy for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which featured George’s Indian-inspired ‘Within You Without You’, a song I think of as the first rock and roll Upanishad.

Interest in Shankar quickly crossed over into jazz, thanks to Richard Bock, whose LA-based World Pacific Records recorded most of Shankar’s albums in the 50s and 60s. Through Bock, Shankar met and performed with jazz luminaries like Bud Shank and Paul Horn, and befriended John and Alice Coltrane, who became so close to Shankar they named their son Ravi (Ravi Coltrane is now a stellar saxophonist in his own right). The Coltranes became serious students of Indian spirituality, and Alice eventually became a swami, running her own ashram in California until her death in 2007. Shankar also influenced, and collaborated with, the renowned composer Philip Glass, who has been a student of Hindu and Buddhist spiritual teachings since the sixties.

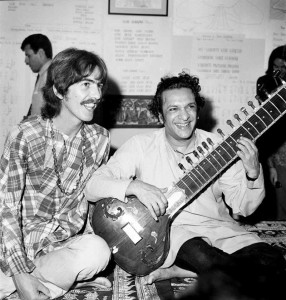

But it was, of course, the maestro’s musical and spiritual influence on George Harrison that shook the world. George discovered the sitar on the set of the Beatles’ movie Help, in 1965. He learned enough to feature the memorable riffs on the opening of ‘Norwegian Wood’, which was released at the end of that year on the Rubber Soul album. David Crosby, whose folk-rock group The Byrds also recorded for World Pacific, was turned on to Shankar by Bock, and he, in turn, told his friend George about him. That led to one of the most significant mentor-student relationships since Socrates and Plato.

In 1966, Harrison spent six weeks in India, studying sitar under the master’s tutelage. The musical results can be heard on several Beatles tracks and attracted enough imitators to birth a short-lived musical subcategory called Raga Rock. Indian motifs would later grace many of George’s post-Beatles solo work. The relationship with his sitar mentor also catalyzed a spiritual quest that would make George about as Hindu as a Liverpool Catholic could possibly be. Shankar gave George books to read. They included Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga, which George said taught him that spirituality was more a matter of direct inner experience than of force-fed dogma, and Autobiography of a Yogi , Paramahansa Yogananda‘s seminal memoir. The excellent documentary about Yogananda, Awake, shows George saying if he hadn’t read that book he “probably wouldn’t have a life, really. I probably would have kicked the bucket or I would just be, you know, some horrible person, with a pointless life. It just gave meaning to life.” George would hand out the book as a gift the rest of his life.

The Shankar-Harrison bond led directly to the watershed moment in Aug., 1967, when the Beatles met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and took up Transcendental Meditation, and a short while later their famous sojourn at his ashram on the Ganges. Musically, the chief result was the White Album. Spiritually, it led to the mainstreaming of meditation and other expressions of Indian spirituality, including today’s boom in hatha yoga and kirtan, the traditional chanting that George put on the pop map withRadha Krishna Temple, the 1970 album he produced with Hare Krishna devotee/musicians.

That powerful mix of music, friendship, collaboration, and spiritual transformation constitutes a unique legacy. The remarkable life of Pandit Ravi Shankar should be celebrated as much for its contribution to the spiritual transformation of the West as for his astonishing virtuosity and his unmatched role in bringing classical Indian music to the rest of the world.